From April 25th New Section

"Pictures from you"

actually Prague 1950

Domains

www.prague-postcards.com

www.pohlednicepraha.cz

www.pohlednice-praha.cz

are for sale,

contact us via mail or via this form

In working out the conception of the contents and pictorial materials included in prime book, I had the guiding intention of offering postcard collectors a book on Prague postcards which all admirers of old Prague have so far lacked, namely a collection of interesting period material and the opportunity to have a complex and focused look at the historical nucleus of Prague which until 1874 was surrounded by a continuous Baroque fortification.

I would like to emphasize the pioneering character of the chapter authored by Milan degen on Prague postcards in which he draws on his many years of research in this field. The pictorial section of the volume includes reproductions of postcards with pictures from six historical Prague quarters or „towns“, but also one chapter on areas which overlap the border between the old and the New Town.

Old Prague | PhDr. Zdeněk Míka, CSc.: Foreword

Postcards are our life-long companions. We encounter them as early as childhood. Usually we find them neatly laid aside in a box, in a cupboard, in the attic where one puts things which are not essentially needed in life, but with which one parts unwillingly. Postcards, together with fairy tale books, primers and the omnipresent television screens, can thus be our first source of acquaintance with the outside world, with its monuments and with the natural beauties of one’s own, as well as other countries. As we grow older, the postcards can remind us of our nearest and dearest, of our friends, of the places where we felt happy and contented. But they can also be study aids, and last but not least, the focus of our collectors’ passion. We Czechs are obviously interested in old postcards of our towns, including, understandably, Prague, the country’s capital and the place which is the richest in historical monuments.

The development of industry and trade, technological innovations, dramatic changes in the social structure of the population, city growth and modernization, all these are characteristic features of Prague and most suburbs (then still outside the city limits) which surrounded Prague in the 2nd half of the 19th century and at the beginning of the 20th century.

Even though Prague changed considerably in this period, it still had to work hard to become the equal of other European metropoles. Of the developing Prague industries, the most important were the machine and later the electrical engineering and automobile industries which all lend Prague the character of a Central European industrial centre. This industrial development was logically followed by a rapid growth of banking and other financial institutions.

However, what changed in Prague in the above period was the image of historical Prague itself. Gradually Prague got rid of its Baroque fortification, some other parts of historical Prague were cleared at the turn of the century, and on the site of the demolished structures appeared new buildings or parks. The ever richer cultural life of the city was boosted by the construction of new theatres, museums and concert halls, in themselves outstanding architectural monuments. The Neo-Renaissance buildings of the National Theatre, the Rudolfinum, the National Museum, the Municipal Museum and the Museum of Arts and Crafts were material symbols of the Renaissance of Czech national life in the 19th century, while the new German Theatre (today’s State Opera) was no doubt a boost to the German-speaking population of Prague. The pseudohistorical styles in architecture were replaced at the beginning of the 20th century by Art Nouveau and by the unique Cubist architecture which had no counterpart anywhere else in Europe.

The demolition of the ramparts sped up the process of integrating Prague with its suburbs, originally independent villages or small towns, economically, politically and culturally, even though in terms of administration most of these municipalities were not joined with Prague until much later.

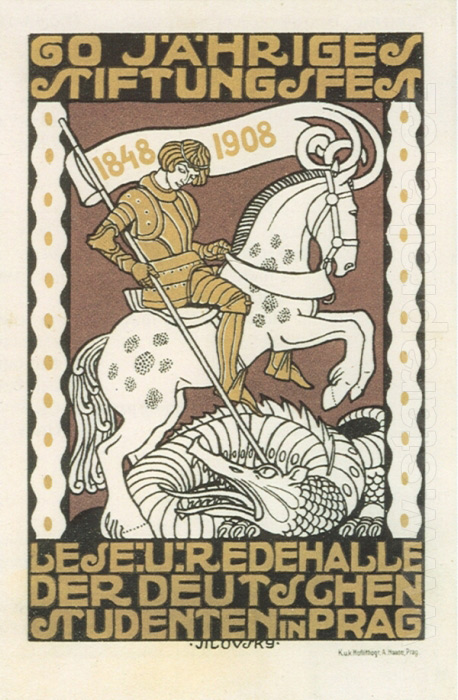

Still, the 19th century saw the incorporation in Prague of such independent municipalities as Vyšehrad, Holešovice-Bubny and Libeň. The needs of the growing city also gave rise to a large-scale city transport system, first by the introduction of horse-drawn trams in 1875, later of electric trams. The city also modernised itself thanks to its electrification and to the replacement of the old gas lighting of Prague’s streets with the Křižík electric arc lamps. Railway transportation underwent its largest growth period even earlier, in the 1860s and 70s. The development of railways was immediately linked with the expansion of postal services which, among other things, included the introduction of non-pictorial postcards, soon followed by picture postcards. All these changes were conducive to the growth of Prague’s population. From the 157 thousand inhabitants in the middle of the 19th century, the number had grown to more than 600 thousand just before the outbreak of the First World War. While no demographic growth occurred in inner Prague (in fact, in some parts of inner Prague the population began to slowly decrease), in the suburban towns outside the limits of Prague, such as Žižkov and Královské Vinohrady, the population growth was mushrooming. At the same time the share of German speakers in the population of inner Prague began to decrease: from 13.7 per cent in 1860 it dropped to a mere 4.6 per cent immediately after the end of the Great War. While the social and cultural life of Prague was largely dominated by its middle classes, the growing number of workers began to be felt too. Due to the impressive upsurge of Czech culture, education and science in the 19th century and early decades of the 20th century, Prague had become a natural centre of the whole Czech nation. One of the most remarkable phenomena of Prague’s life in this period was the fruitful coexistence of three national cultures: Czech, German and Jewish, and their mutual interaction. This held for music, the graphic arts and the theatre, but most importantly for literature. It was precisely at the turn of the century that Prague was the home of a number of world-famous German writers of Jewish origin, of whom Franz Kafka is certainly the best known.

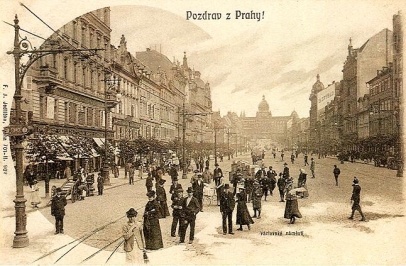

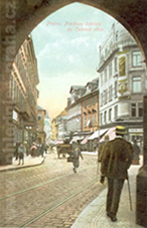

Such then was Prague at the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. Its atmosphere was captured not only in period Baedekers, memoirs, newspapers and old photographs, but also in postcards which reproduce old pictures through a number of techniques. In some cases we know the original, either a photograph or a painting which became the basis of these postcards. However, in many other cases we know nothing of the originals, and the preserved postcard is a unique piece of evidence about the history of our capital. Even so, no matter in which of the two categories the postcards in this book fall, they provide the reader with many invaluable details about the place and the time. They give us truthful information on the appearance and architecture of streets, squares and individual buildings, sometimes no longer existing. The postcards are therefore a source of knowledge about old Prague from a time when a series of clearances seem to have changed it beyond recognition. This holds especially for the pictures of the former Jewish ghetto and for the area of Mariánské Square in the Old Town.

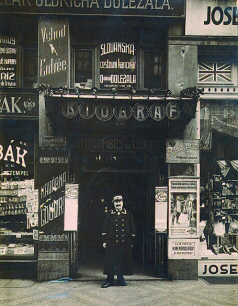

The period postcards render to us the sedate, almost sleepy atmosphere of some of these streets and corners, as well as the hustle and bustle of the main commercial streets and market places. The characters in the postcards represent all social and age categories of Prague’s population. The varied advertisements on the buildings and above the shop windows are remarkable both for their variety and the information they carry. The postcards also provide intriguing documentary material about all kinds of events, such as the visits of V.I.P.s, funerals, catastrophes, ceremonies, exhibitions, sporting activities, and many others. Last but not least, they are also invaluable documents of everyday life: we can see in them the market people in the Havelské Marketplace, various Prague types and figures, such as those gambling in the Imperial Royal Lottery, patrons of restaurants and pubs, and dozens of other curiosities.

We learn from the postcards about the old Prague public transportation system, and about its metamorphosis when horse-drawn street cars began to be replaced by electric trams. We can see how the streets are filled with horse-drawn carriages, two-wheeled carts, and also with the first automobiles. We can follow in the postcards the gradual changes to the Vltava embankments, the rise of new bridges across the river, as well as ship transport on the Vltava. In other words, we can see in the postcards the birth of a modern metropolis.

Looking at old Prague postcards is certainly a joy not only for city and art historians, for ethnographers, for lovers of historical and artistic monuments, for stampcollectors, tourist or postcard collectors. It is pleasure for those of us who love the Czech capital, which is so closely connected with Czech history and statehood. I wish all of these great pleasure and joy from this remarkable volume.