222 - The Old-New Synagogue and the Jewish Town Hall

The particular architectural character of the Jewish ghetto, which was narrow and cramped, never inspired Prague’s postcard producers. An exception to this is the Old Jewish Cemetery, and the complex of the Old-New Synagogue and the Jewish Town Hall in Rabínská Street. Featured in this postcard are the latter two buildings. The picturesque character of the buildings is accentuated by the atmosphere of a winter evening. COLOURED LITHOGRAPH. AROUND 1898 |

223 - A panoramic view of the houses on the Old Town part of the river bank neighbouring the Jewish ghetto

Interestingly, the picture shows the contrast between the traditional economic character and the modern representative character of the area. On the right, we can see the architecturally imposing Rudolfinum, while behind the building there is a row of small peripheral houses, former saltpetre plants, penitentiaries, sawmills and wood storehouses. The Old Town part of the river bank is separated from the heavily built-up ghetto, by Sanytrova (today 17. listopadu) Street. in the background we can see the ghetto which is visually demarcated by the Church of the Holy Spirit, the Church of St Salvator and the Church of St Nicholas. EXTRA-LARGE POSTCARD. PICTURE AROUND 1895. K. BELLMANN, 1898 |

224 - A view of the Jewish Town Hall and of a part of the Old-New Synagogue in Rabínská Street from the north

The originally Gothic Town Hall was presumably built as early as in the 16th century. Later it was rebuilt in the Renaissance style, and in the 1760s it acquired a new Baroque appearance. The Baroque reconstruction was based on the project by J. Schwanitzer (also called Schlesinger). The front of the Town Hall faces Rabínská Street, and it is one of the few old ghetto buildings with a Baroque decorative facade, which was quite common in other parts of Prague. A part of the building is a wooden tower with a Hebrew clock. In 1908 the construction was extended by three floors. The Jewish Town Hall is the only secular building of the ghetto which was saved during the slum clearance (see picture 273). PHOTOTYPE. PHOTOBROM W FIRM, AROUND 1905 |

225 - The Old-New Synagogue, built in the last quarter of the 13th century

Not only is it one of the oldest European Jewish monuments, it is also one of the earliest Gothic buildings in Prague. The Synagogue has always been the religious centre of the ghetto. Its particular role and importance was emphasized by the fact that it stood apart from other buildings, unlike other Prague synagogues. There was a small marketplace in front of its back facade - it was the only area of the ghetto which could be called a square. On the right side of the postcard we can see a part of house No. 220, the so-called Wedeles House, on the corner of Červená and Rabínská Streets. It is one of the five ghetto synagogues which survived the slum clearances. COLOURED PHOTOTYPE. AROUND 1900 |

226 - A view of Červená Street from the south-west

The part of the street we can see formed the northern part of a small square behind the Old-New Synagogue. On the right the street leads to Cikánská Street (see picture 228). The name of the street (červená means red) is linked to the red colour of the meat stores which used to be here. At the time this picture was taken, the meat stores had moved to the northern part of Masařská Street in front of the Velkodvorská (Grand Court) Synagogue. The impressive Moscheles House, No. 167, dominates the centre of the street. Its Baroque terrace was particularly attractive to photographers who tried to capture the unique character of the disappearing ghetto. The cracked plaster shows the extent to which the building had been neglected. PHOGOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE BEFORE 1903. Z. REACH, 1920s |

227 - Small square behind the Old-New Synagogue

Used to serve as a marketplace, called either the Dřevěný (Wood) or the Řeznický (Meat) Square, depending on the predominant goods in the market. The picture was taken after demolition of the buildings behind the synagogue, especially after No. 164, on the right of Červená Street, had been pulled down. This opened a view to the possibly most bizzare building complex of the ghetto - the Baroque Moscheles House, No. 167, in the northern part of the Square. Differences in heights of the buildings, some houses having several storeys, others only one, were typical of the ghetto. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE BEFORE 1903, Z. REACH, 1920s |

228 - A vista of Červená Street

A vista of Červená Street, from its intersection with Cikánská Street towards the little square behind the Old-New Synagogue. The postcard shows a typical ghetto street. Because of its east-west direction the sun could penetrate the street, while the streets running north-south were darker. On the right, behind the house No. 172, stands the Moscheles House, No. 167. It is an imposing four-storey Baroque building with a terrace. Behind it is the side wall of the originally Gothic, later Renaissance, Wedeles House, No. 220, standing on the corner of Červená and Rabínská Streets. During the flood which hit the ghetto in 1890, the water reached the middle of the windows on the ground floor. The houses in Červená Street were pulled down between 1903 and 1905. PHOTOTYPE. K. BELLMANN, 1897 |

229 - Střelná Street

Part of the Old Town between Dušní and Cikánská Streets, as seen from Dušní in the direction of Cikánská. There were many cul-de-sacs and houses with right of way beneath them in the Jewish ghetto and the neighbouring parts of the Old Town. One of these houses was the famous four-storey house with a built-on gallery - U Šišlingů, No. 890, which was situated between Střelná and Cikánská Streets. This house and others surrounded the Church of the Holy Spirit and formed a narrow strip of Christian ground which separated the eastern and western parts of the ghetto. The street on the left in front of house No. 891, where V. Kratochvíl kept a store, leads to a small square in front of the Church of the Holy Spirit. The long house, No. 889, with its interesting, uneven front (on the right) stands on the corner of Dušní Street. Both houses on the right side of the street were demolished between 1909-1911. The house on the left was one of the last three original houses that surrounded the Church (see picture 233) and it was demolished three years later. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE BEFORE 1909. Z. REACH, 1920s |

230 - The Spanish Synagogue

On the corner of Dušní and Vězeňská Streets which was designed by I. Ullmann and J. Niklas. It was built in the second half of the 19th century in the Moorish style, replacing the original and oldest synagogue called the Old School in a Jewish settlement of the same name. The Old School Synagogue and several Jewish houses surrounding it formed a separate area which never merged with the western part of the ghetto. Most of the houses in the area were demolished in 1911 and 1912. Behind the synagogue, on the raised ground on the corner of the restructured U staré školy (The Old School) Street and Vězeňská Street, we can see the construction of house new No. 115, designed by J. Dneboský. The house on the corner with the Neo-Classical facade was the last surviving of the original houses and it was demolished in 1935. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1912. Z. REACH, 1920s |

231 - A view of the northern part of Cikánská Street in the direction of Janské Square

Cikánská was a side street of the Josefov Quarter which ran through the ghetto from north to south. The houses were not particularly architecturally imposing and, like most of the other houses in the ghetto, they had very simple facades. Typically, there were cornices between the floors and ledges above the windows, which protected the window panes which were inserted towards the front, in the Baroque fashion, and were thus exposed to the rain. On the left, behind houses Nos. 190, 191 and 192 and in front of No. 884 (the house with the street- lamp) Rabínská Street opens into Cikánská. In the background, we can see a part of a two-storey house, No. 875, in Janské Square (see picture 139). The houses on the left side of the street were demolished in 1905 and 1906. PHOTOGRAPH. 1902 |

232 - Vězeňská Street, as seen from Kozí (Goat) Square

On the right, there are the original buildings of the area around the Old School, on the left, there are houses built on elevated ground after the slum clearance. The two ground levels are separated by railings and connected by stairs. The street on the right, which is lined by buildings Nos. 860 and 150, leads to the Old School Synagogue. The two-storey rectory of the Church of the Holy Spirit, No. 894, standing behind four houses, Nos. 147, 146, 144 and 143, was demolished as late as in 1933. The other houses were pulled down in 1912. In the northern part of the street on the left there are new houses, new Nos. 910-914, built in 1905 and 1906. In the background, we can see two houses - new No. 66 on the left, built in 1904 on the corner of Mikulášská and Široká Streets and designed by J. Vejrych, and new No. 124 on the right, behind the rectory, built in 1908 on the corner of Široká and E. Krásnohorské Streets and designed by F. Niklas. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1909. Z. REACH, 1920s |

234 -A view of Dušní in the direction of the Church of the Holy Spirit

We can see the Christian and Jewish parts of the area merge, and two narrow streets, the Jewish Masařská Street on the right and the Christian Bílkova Street on the left, lead into Dušní Street. On the left, in the foregound, there is the two-storey house No. 861, U Bílků, decorated by a Baroque cartouche, which gave its name to the side street. (Originally Bílkova Street was a cul-de-sac, later it was connected with Cikánská Street after houses 855 and 856 were demolished in 1901 and 1902, see picture 143.) Nos. 186, 888, 889, 893, on the right, next to the Church of the Holy Spirit, were demolished between 1911 and 1914. in the front, there is a public well with interest ing roofing. FOUR-COLOUR AUTOTYPE. AFTER AN OIL-PAINTING BY J. MINAŘÍK, 1907. F. J. JEDLIČKA, 1915

|

235 - A courtyard of No. 156 in the area around the Old School

The houses in the district were built in the Middle Ages and had Renaissance galleries and Baroque attics. There were many busy stores and businesses centred around the spacious courtyard, which resembled a small square. No. 156 was, in contrast to the cramped neighbouring houses, spacious and sunny. The photographer’s intention was not, apparently, to portray people, he was interested in the sunlit courtyard and none of the people in the postcard seem aware of the photographer’s presence, with the exception of the woman at the wash-tub who has just finished doing her laundry. In the background we can see the wall of house No. 287. The picture was taken a short time before the demolition of the buildings in 1911. COLOURED PHOTO-LITHOGRAPH. PICTURE 1908. MONOPOL, PROBABLY THE 1930s

|

236 - House Nos. 180 and 182 on the corner of Masařská Street and Cikánská Street

Originally, there was a lovely, architecturally varied courtyard and a Baroque gallery with an external roofed staircase, which was one of the most typical architectural elements to be found in the Jewish ghetto. This house, like many others, originally belonged to the banker J. Bassevi. It may have been one of those houses built on the periphery of the ghetto, which belonged to Protestant exiles and which Bassevi bought after 1621. Before the slum clearance, the courtyard was a popular motif for painters and photographers interested in depicting the disappearing parts of Prague. The house was demolished in 1910. FOUR-COLOUR AUTOTYPE. AFTER AN OIL-PAINTING BY J. MINAŘÍK, 1907. F. J. JEDLIČKA, 1915 |

238 - The southern part of Hampejská Street with Nos. 229, 231, 232 and (behind the tree) 234

The picture could have been taken only after the opposite house, No. 230, was demolished in 1907. The wall on the right lines the Old Jewish Cemetery. The street makes a curve to the right along the Cemetery and the Klausen Synagogue and then, following a straight section, leads into Rabínská Street (see picture 237). The houses in Hampejská have a common architectural motif - hinged windows, which suggests a mediaeval origin of the buildings. As the name implies (Brothel Street), Hampejská was a centre of prostitution in the ghetto. However, this was not the only place in the ghetto and the neighbourhood where prostitution was practiced. There were brothels in V Kolnách, Valentinská and U Milosrdných Streets (see picture 147), on the corner of Josefovská and Kaprová Streets, in the U Denice pub in Rabínská Street and in other places. The houses in Hampejská were pulled down in 1909./p> PHOTOTYPE. K. BELLMANN, 1909 |

239 - Buildings Nos. 221, 222, 223 and 225 (from the left) in Rabínská Street

Facing the Old-New Synagogue between Břehová Street (in the foreground) and Hampejská Street (in the background) show the typical architectural style of the ghetto, marked by simplicity and sobriety. The houses were built and some reconstructed in the first half of the 19th century. At that time, this section of the western part of the ghetto was full of construction and reconstruction activity - houses were being enlarged and every free space was used to erect a new building. The picture shows one of the last strips of old buildings in the area. In the background there is the southern part of the newly built Široká and Mikulášská Streets. The old houses in the picture were demolished in 1909. In 1910 and 1911, a modern appartment complex, new No. 41, was built in their place - it was again marked by a sober architectural tone and was based on designs by R. Klenka and F. Weyr. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1909. Z. REACH, 1920s |

240 - The western end of Josefovská Street

Should the photographer have moved forward from the standpoint he has adopted in picture 241 behind the small shops in the Cemetery wall, he would have seen exactly the same scene we see in the above picture. On the right, behind house No. 20 with a street lamp, there is a cul-de-sac - Pinkasova Lane, which runs vertically towards Josefovská and leads to the Pinkas Synagogue (see picture 248). Behind Pinkasova Lane stands house No. 8 and other buildings of Valentinské Square, which can be seen in picture 242. The posters on No. 19 (on the left) announce that the store of K. Lang has moved to a different part of the street. Three men and children pose for the photographer. The inscription on the postcard identifies the man standing in the middle as the builder Lehký (this is probably Emanuel Lehký, businessman in the field of sewerage systems). The slum clearance in this part of the ghetto took place in 1908. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1907. Z. REACH, 1920s

|

242 - Valentinské Square

Pat the intersection of Josefovská and Kaprová Streets (on the right) and Valentinská Street. The photographer is standing at the end of Valentinská. This small square was one of the places where Jewish and Christian Prague mixed. The architec turally varied houses, Nos. 11, 10, 9 and 8, in the northern part of the Square were administratively part of Josefov. Behind No. 8 (on the right) ran Pinkasova Lane, which led to the Pinkas Synagogue. The houses were demolished in 1907. Today, part of the building of the Philosophical Faculty of Charles university and the northern part of new Valentinská Street stand on the site. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1902. Z. REACH, 1920s |

243 - The second-hand store which belonged to Moses Reach

It was built into a wall which divided the western end of Josefovská Street from the Old Jewish Cemetery (see picture 241). There were many such second-hand stores in the ghetto. According to the writer I. Herrmann, who in 1902 writes about life in the Prague ghetto, there was hardly an empty space between the walls which was not used as a second-hand store. All sorts of goods were available in the Jewish second-hand stores: antiques, rare books, clothes, hardware and bric-a-brac. Some dealers had stores, others carried bundles or pushed their goods, priced at one or two guldens, on carts. They walked the streets of the ghetto and at the end of the day they might make a profit of a few kreutzers, which assured a poor living. PHOTOGRAHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE AROUND 1898. Z. REACH, END OF THE 1920s |

245 - A part of the northern side of Josefovská Street

Between Rabínská Street (on the left) and Šmilesova Street (on the right, this street is not in the picture). Josefovská was the widest street of the ghetto. Its original name was Široká („wide“), and this is also the name of the new street which was built in its place. Although Josefovská Street was wide, this picture was taken only after the opposite part of the street had been pulled down in 1896-1898, which enabled the photographer to stand at a distance. On the left, on the corner of Rabínská Street, stands No. 264, on the opposite corner No. 95. Apparently the latter func tioned as one of the most elegant and luxurious brothels in the ghetto and in the whole city of Prague. It was run by one J. Friedmann who managed to be both a detective and conspirator. The houses in the picture were demolished in 1905. In picture 258 we can see the demolition of the three houses on the right, Nos. 105 (a part), 104 and 98. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE AROUND 1900. Z. REACH, 1920s |

246 - A different part of the northern side of Josefovská Street

In the middle of the postcard there are four houses, Nos. 127, 126, 125 and 124 between Šmilesova Street (on the left) and Cikánská Street (on the right). The house on the corner, No. 127, is standing on the site where Pařížská Street runs today - see picture 268. Josefovská Street then runs along No. 900 on the corner of Cikánská and Kostelní Streets and leads to the intersection of Dušní and Vězeňská Streets (on the right, just off the picture). Although this was the busiest street of the ghetto, the houses were not architecturally impressive as most of the buildings underwent alterations during the 19th century. Due to the intensive attitude towards the demolitions between 1903 and 1905, without any archeological research, much precious information about the architectural development of the ghetto was lost. The opposite, southern part of the street was no longer extant at the time of taking this picture. But we can see it in the following postcard. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE AROUND 1900. Z. REACH, 1920s |

247 - The southern side of Josefovská Street

The street was 400 metres long, thus it was the longest thoroughfare in the Jewish Town. It led to Kaprová Street in the west, and to Vězeňská Street in the north-east. The picture was taken a short time before the demolitions in this part of Josefovská Street started, and it captures the liveliness of the street. The three houses on the right are Nos. 92, 91 and 90. Rabbi Löw (1520-1609), the supposed creator of the legendary Golem, used to live in a house standing on the site of No. 90. The original Meislova Street leads into Josefovská behind these houses. In the background, in front of No. 115, protruding into the street, we can see the building of the New Synagogue, No. 113, distinguished by its high windows. All the buildings in this picture were demolished between 1896 and 1898. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1896. Z. REACH, 1920s |

Rabbi Löw

Judah Loew ben Bezalel, alt. Loewe, Löwe, or Levai, (c. 1520 – 17 September 1609)[1] widely known to scholars of Judaism as the Maharal of Prague, or simply The MaHaRaL, the Hebrew acronym of "Moreinu ha-Rav Loew," ("Our Teacher, Rabbi Loew") was an important Talmudic scholar, Jewish mystic, and philosopher who served as a leading rabbi in the city of Prague in Bohemia for most of his life. Within the world of Torah and Talmudic scholarship, he is known for his works on Jewish philosophy and Jewish mysticism and his work Gur Aryeh al HaTorah, a supercommentary on Rashi's Torah commentary. The Maharal is the subject of a nineteenth-century legend that he created The Golem of Prague, an animate being fashioned from clay. Rabbi Loew is buried at the Old Jewish Cemetery, Prague in Josefov, where his grave and intact tombstone can still be visited. His descendants' surnames include Loewy, Loeb, Lowy, Oppenheimer, Pfaelzer, and Keim. The Golem of PragueThe most famous golem narrative involves Judah Loew ben Bezalel, the late 16th century chief rabbi of Prague, also known as the Maharal, who reportedly created a golem to defend the Prague ghetto from antisemitic attacks[8] and pogroms. Depending on the version of the legend, the Jews in Prague were to be either expelled or killed under the rule of Rudolf II, the Holy Roman Emperor. To protect the Jewish community, the rabbi constructed the Golem out of clay from the banks of the Vltava river, and brought it to life through rituals and Hebrew incantations. As this golem grew, it became increasingly violent, killing gentiles and spreading fear. A different story tells of a golem that fell in love, and when rejected, became the violent monster seen in most accounts. Some versions have the golem eventually turning on its creator or attacking other Jews. The Emperor begged Rabbi Loew to destroy the Golem, promising to stop the persecution of the Jews. To deactivate the Golem, the rabbi rubbed out the first letter of the word "emet" (truth or reality) from the creature's forehead leaving the Hebrew word "met", meaning dead. The Golem's body was stored in the attic genizah of the Old New Synagogue, where it would be restored to life again if needed. According to legend, the body of Rabbi Loew's Golem still lies in the synagogue's attic. Some versions of the tale state that the Golem was stolen from the genizah and entombed in a graveyard in Prague's Žižkov district, where the Žižkov Television Tower now stands. A recent legend tells of a Nazi agent ascending to the synagogue attic during World War II and trying to stab the Golem, but he died instead. When the attic was renovated in 1883, no evidence of the Golem was found.[10] A film crew who visited and filmed the attic in 1984 found no evidence either. The attic is not open to the general public. Some strictly orthodox Jews believe that the Maharal did actually create a golem. Menachem Mendel Schneerson (the last Rebbe of Lubavitch) wrote that his father-in-law, Yosef Yitzchok Schneersohn, told him that he saw the remains of the Golem in the attic of Alt-Neu Shul. Rabbi Chaim Noach Levin also wrote in his notes on Megillas Yuchsin that he heard directly from Rabbi Yosef Shaul Halevi, the head of the Rabbinical court of Lemberg, that when he wanted to go see the remains of the Golem, the sexton of the Alt-Neu Shul said that Rabbi Yechezkel Landau had advised against going up to the attic after he himself had gone up. The evidence for this belief has been analyzed from an orthodox Jewish perspective by Shnayer Z. Leiman. Source and more informations : |

248 - The cul-de-sac Pinkasova

It originates in Josefovská Street and leads to the Pinkas Synagogue (see picture 249) and to the Old Jewish Cemetery. On the right, we can see the bay of the synagogue projecting into the street, in the background we see a part of the Museum of Decorative Arts, built on a piece of land belonging to the Cemetery. It was in this narrow and quiet lane that the numbering of houses in the ghetto began, with the house of the Jewish Burial Society, No. 1. (in the back, in front of the wall). The numbering existed already before 1770. The houses on the left side of the street, Nos. 1 - 5 and No. 8 on the corner, date back to the second half of the 18th century and were built after the fire of 1754. On the right there is a house with a street lamp, No. 20. we saw the builder Lehký posing in pictures 240 and 244. His appearance in all these photographs can be explained by his involvement in the slum clearances. The houses in this street were demolished during 1907 and 1908. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1906. Z. REACH, 1920s |

249 - The western wall of the Pinkas Synagogue, No. 23, originally facing Pinkasova Lane

The synagogue was built in the second half of the 15th century in the Late Gothic style. It takes its name from Rabbi J. Pinchas, the supposed founder. It was often reconstructed, the most significant alterations being in the Renaissance style which it has retained till today. In 1908 the surrounding houses were demolished and the terrain elevated by about 2 metres, and so the synagogue became fully visible. On the left we can see trees behind the wall of the Old Jewish Cemetery. It is remarkable that the Synagogue was not destroyed during the slum clearances, although its corner projects into the newly built Široká Street. The synagogue underwent a number of reconstructions from the end of the 19th century. Today the synagogue serves as a memorial to all the Bohemian and Moravian jewish victims of the Nazis. PHOTOTYPE. K. BELLMANN, AROUND 1909 |

250 - The Jewish baths existed in the ghetto from the 15th century

They were built between the cul-de-sac Goldřichodvorská and Sanytrová Streets, on the periphery of the ghetto. The bath in this picture was situated in the block between the nameless lane leading to the Old jewish Cemetery and Sanytrová Street. This bath was not the only one. Another bath was situated in the house neighbouring the New Synagogue in Josefovská. The bath had an important cleansing, but also ritual, function in the life of the jews. The two buildings, No. 274 (on the left), and the bath itself, No. 208 (on the right), were demolished in 1905 and in 1908 respectively. Baths were often situated next to synagogues, and they were a favourite motif of photographers, often appearing on postcards. FOUR-COLOUR AUTOTYPE. AFTER AN OIL-PAINTING BY J. MINAŘÍK, AROUND 1905. F. J. JEDLIČKA, 1915 |

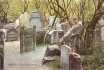

251 - The Jewish cemetery

Was founded in this place in the first half of the 15th century as a replacement for the original Jewish cemetery, situated in the area of what is today Vladislavova Street in the New Town. Apparently, there was an even older burial ground, founded as early as in the 11th century, next to a Jewish settlement near the present Újezd in the Lesser Town. The new cemetery originally covered a smaller area, but it was gradually enlarged after more land was bought. However, once no more land was available, people had to be buried on top of one other in several layers. The tombstones were usually raised from the deeper layers to the top and so today they are crammed, one next to the other. This is a typical feature of the Prague Jewish cemetery. There are as many as 12 thousand tombstones, the oldest tomb being that of the doctor, poet and rabbi Avigdor Kara (1439). The last burial was in 1787. COLOUR PHOTOTYPE. UNIE PRAGUE, AROUND 1905 |

252 - The tripple corner of Úzká Street (on the left) and Jáchymova Street (on the right)

Two Renaissance houses, exceptionally large in the context of the ghetto, No. 61, U Vápenice, and No. 62, Trefanovského, were joined, forming an interesting small square. The houses had simple facades, restored in the 19th century. There were small stores on the ground floors and a gas lamp-post and a well in the middle of the square. The shop on the corner of the house on the left belonged to A. Plass, who moved in 1897, when the house was demolished, to No. 32 (see picture 253). No. 61, U Vápenice, served as the first college in Prague after Charles IV bought the house from the Jew Lazarus and then donated it to the university. FOUR-COLOUR AUTOTYPE. AFTER AN OIL-PAINTING BY J. MINAŘÍK, BEFORE 1897.

F. J. JEDLIČKA, 1915

|

253 - The corner of Kaprová and Úzká Streets

No. 32 belonged administratively to the Old Town, but the house behind it, No. 59 (on the right), was already part of josefov. On the left, the Christian Kaprová Street runs west towards the bank, on the right we can see the Jewish street called Úzká. The picture was taken from the railed-off, elevated ground on the site of the already demolished house No. 30. we can see A. Plass’s general shop (see picture 252) bearing signs advertising Maggi (a spicy sauce), Kolínská káva (coffee), and V. Gráf’s shoe-shop with a display of wellingtons. The original, pre-clearance street was, as its name Úzká (narrow) indicates, only 3 metres wide. The house on the corner was demolished in 1905. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE AROUND 1903. Z. REACH, 1920s |

254 - The western side of the busy Úzká Street with a view towards Josefovská Street

The original name of the street was Zlatá (Golden). As in the previous postcards, the photographer was standing on the site of already demolished houses. In this case, he stood at the opposite side of the street, several metres south of the Meisl Synagogue, now standing solytarily in the midst of the cleared area. The high, originally Gothic houses never allowed any sun to penetrate the narrow street, and so the place was gloomy and depressing. However, this picture shows facades flooded with sunlight, rows of high windows and, on the ground floor, shops with all sorts of goods. At No. 55, on the left, we can see a second-hand clothes shop, further on, at No. 53, there is a pottery store, with a display of jugs, mugs and various china goods. The facade of No. 53 has apparently been recently restored, and itstands in contrast to the shabby facades of the neighbour ing houses. But even this house was demolished in 1905 during the clearances in this street. In the middle of the street there stands a four-storey house, No. 50, with three remarkable hinged dormer-windows. No. 264 in Josefovská Street closes the view of the street (see picture 245). PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1902. Z. REACH, 1920s |

255 - Meislova Street

Meislova Street, as seen from Staroměstské Square towards the north (picture 257 shows the street from the opposite side). Meislova originated at the square next to the Church of St Nicholas. It made several sharp turns before it led into Josefovská Street. The picture shows the widest part of the street, near Kostečná Street. On the right, there is one of the two Renaissance palaces belonging to the banker J. Bassevi, No. 74. They did not form part of the ghetto until the 17th century. No. 78, U rajských jablek (The Paradise Apples), behind Kostečná Street, served as a hotel - the hotel Flussek. A passage-way ran through the next house. It led to the New synagogue and to Josefovská Street. The ongoing Meislova Street, which curved to the left, led to Josefovská and to the Meisl Synagogue respectively. The Synagogue is hidden from view by the houses numbered 75, 76 and 77 on the left which were destroyed in the first stage of clearances during the years 1896 and 1897. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1895. Z. REACH, 1920s |

256 - The Meisl Synagogue, originally built in the Late Renaissance style

It was founded in 1590 by Mordechai Meisl, who was a wealthy businessman and the primate of the Prague Jewish Community. The Synagogue stood in the block between Jáchymova and Josefovská Streets. It could be reached from Meislova and Úzká Streets. After the houses in the eastern part of Úzká Street were destroyed, a new street was built on the site. It bore the name Maiselova, somewhat altering the original spelling of the name. The picture shows the new Maiselova Street and the decorative western front of the Synagogue after its 1893-1905 Neo-Gothic reconstruction. The houses surrounding the Synagogue were built in the first five years of the 20th century. PHOTOTYPE. F. J. JEDLIČKA, AROUND 1907 |

257 - The original Meislova Street, in the direction of Staroměstské Square

No. 935, on the corner of Meislova and the Old Town Square, closes the view. House No. 935 and the neighbouring No. 934 were the first houses to be demolished in Meislova in 1896 (see pictures 259 and 261), thus launching the whole clearance project. Mikulášská Street was later built on this site approximately along the line of the south ern part of the original Meislova Street (see pictures 268 and 269). In the postcard, we can still see the Renaissance palace, No. 73, belonging to the banker J. Bassevi (on the left), and behind it, houses Nos. 72 and 71. On the right, on the corner of Jáchymova Street, there is No. 70 and next, there is a small two-storey house with an open staircase, No. 277, which served as a customs-house (this is where theexcise tax - a tax levied on food at the border of the Old Town and the Jewish Town was collected). Beyond the customs-house stands the Benedictine Monastery. The whole street was demolished in 1896 and 1897. PHOTOGRAPHIC POSTCARD. PICTURE 1895. Z. REACH, 1920s |

top of the page history the Clearance of Josefov postcards the Clearance of Josefov |