PhDr. KATEŘINA BEČKOVÁ: THE JEWISH TOWN - JOSEFOV

The origins, eventful history and the extensive clearance of Prague Jewish Town represent some of the most interesting periods of the history of settlement and housing in Prague. The ghetto still attracts today throngs of tourists who visit the few remaining monuments and try to absorb the magical ambience of this place.

As most of the old buildings of the former ghetto were demolished without any archeological or civil engineering research, records on the oldest settlement at this site on the right bank of the Vltava ceased to exist. We are not sure whether this area was originally inhabited by Christians and when it was exactly that the Jews came to this location. Because of the absence of material records we are entirely dependent on contentious written documents. The activity of Jewish merchants was documented in the first written record about Prague by the Arab-Jewish merchant Ibrahim Ibn Jakub as early as 965. What we cannot infer from the above document is whether the Jews had been settled in Prague by then and where. Cosmas chronicles the Jewish settlement as to 1091 in the area of the so-called Vyšehrad path. I.e. in the vicinity of the oldest thoroughfare passing through the inhabited Old Town and the future New Town, heading towards Vyšehrad; its precise location remains uncertain. At that time Jewish settlement is recorded on the left bank of the river Vltava in the area of the Lesser Town, presumably on the site of what is today Mostecká Street.

The area of the future ghetto had probably been inhabited prior to the arrival of the Jewish population or before the expansion of the ghetto as, roughly in the direction of what is today Široká Street, there was an important trade route linking the Vltava ford with the settlement of German merchants at Poříčí, in the vicinity of which was another major ford linking the north and north-east routes. The Vltava ford was located on the site of the present Mánes Bridge. It is assumed that the settlement first saw Jews arriving in Bohemia from the east (from Byzantium) who founded the Old School Synagogue (today the location of the Spanish Synagogue). It was not until 1170 that the first stone bridge was built - the Judith Bridge (the predecessor of Charles Bridge). Consequently the major trade route moved southwards, so that it led outside the territory of the future ghetto, where new space was made for the extension of the settlement by the Jewish community.

In the last quarter of the 13th century, i.e. at the time when the Staronová (Old-New) Synagogue, one of the oldest Gothic monuments in Prague, was founded, this location had already seen the established settlement of Jews who came to Prague from western parts of Europe. It is essential to point out that the eastern part of Prague ghetto, which was concentrated around the Old School Synagogue, never merged with its western counterpart settled around the Old-New Synagogue, to create a coherent unity. The two settlements remained separated by an island of Christian houses and the Church of the Holy Spirit.

The mediaeval ghetto must have had to face frequent anti-Semitic feeling which, e.g. in 1389 and 1422, during the Hussite uprising, and in 1448, grew into pogroms. Six gates segregated the territory of the ghetto from the Christian world. Despite this measure the limits of the ghetto were not demarcated consistently and properties invariably passed from jewish landlords to Christian ones and vice versa.

The first half of the 16th century saw a dramatic period in the life of the Prague Jewish community. Ferdinand I responded to the insistent claims of the Old Town burghers who accused the Jews of fraud, and expelled the Jewish population from the country in 1541. The deadline of the exodus was postponed several times and many wealthy Jewish families purchased expensive safe-conducts permitting residence in Prague. Most of the Jewish community, however, left Prague within two years. Those Jews who stayed had to wear visible identification. In 1557 the safeconducts were abolished and the whole Jewish population was expelled, again with one year’s notice. The houses of the Jewish Town were sold to Christian craftsmen and the synagogues converted into Christian churches. Nevertheless, the Jews managed to postpone the one year notice rule until 1567 when Maximilian II acknowledged the original privileges of all permanently settled Jewish families; new Hebrew inhabitants, however, were banned from settling.

After years of leading an uncertain existence the ghetto experienced the greatest prosperity and success in its history. During the reign of Rudolf II the Jewish privileges were acknowledged once again, in 1577, and the ghetto was gradually extended by means of purchasing new properties and it was enhanced by new building within its own boundaries. This building activity at this time is linked with the name of the leader of the Jewish community, Mordechai Meisl (1528-1601), who was also a banker of Rudolf II. He established a Talmudic school, the Klausen Synagogue and a hospital with baths in 1564 in the vicinity of the Jewish cemetery. In 1568 he participated in the construction of the Jewish Town Hall with a Town Hall Synagogue (the High Synagogue) and in 1591 he acquired the right to build a private synagogue of his own (the Meisl Synagogue). He also purchased a garden in order to extend the cemetery and he had the ghetto streets paved from his own funds.

The Rudolfine period is linked with the figure of the legendary Rabbi Löw (Jehuda Liva ben Becalel, 1520-1609), who did not live in Prague until the second half of his long life. His erudition was outstanding and he was renowned in the Jewish world of the time as the greatest specialist in the Talmud. However, he was also interested in the natural sciences, particularly astronomy and astrology. The most famous legend relating to the Jewish Town refers to him as the creator of an artificial being - the Golem. Rabbi Löw’s connections with Rudolf II have not been substantiated by historians. The gravestone of this learned man has been one of the most visited sites in the Old Jewish Cemetery.

Meisl’s successor at the court of Rudolf II was another wealthy Jew, Jakub Bassevi (1580-1634). He was the first Jew in the Habsburg Monarchy to be promoted to aristocratic status and acquired the title of von Treuenberg. After the defeat of the uprising of the estates he made a profit through purchasing the houses of the exiles and thus extended the ghetto by about three dozen buildings. In 1620 the Emperor presented two mansions in Třístudniční Street (the pre-clearance Maiselova) to Bassevi who had them rebuilt into a late Renaissance palace with a bay courtyard, which is probably the only building in the ghetto for which the use of the word palace is appropriate.

The second half of the 17th century saw a vast inflow of people, particularly in connection with the danger posed by the Turks and the expulsion of Jews from Vienna in 1670. Amounting to 11,000 inhabitants, the Prague ghetto constituted one of the most densely populated Jewish quarters in Europe at that time. However, before the end of the century the time of prosperity, expansion and new housing projects was terminated bitterly by two major catastrophes. In 1680 the overpopulated ghetto was decimated by a plague epidemic and nine years after this disaster it completely burnt down.

In July 1689 an allegedly French arsonist set fire to Kaprová Street in the Old Town. The conflagration spread to the entire Jewish Town, where all 318 buildings burnt down, in the adjoining areas of the Old Town, however, even more buildings were destroyed. The destroyed and uninhabitable ghetto inspired the idea that this location should not be restored and that a different area on the outskirts of Prague should be reserved for the Jewish population. Finally, however, the restoration of the ghetto was permitted, but with a number of conditions: the streets were to be straight and extended, the buildings were to be made of stone only, and the number of settled Jewish families would be subject to a limitation. Nevertheless, for practical reasons the ghetto was rebuilt on the same foundations and to the same ground plan of the street network, for it would have been inefficient to have demolished those solid stone structures which survived the fire.

The gradual renovation of the ghetto was not completed until 1703. In the same period the number of its inhabitants exceeded 11,000, as it had done before the plague epidemic, and it was roughly equal to the population of the Old Town. This fact goaded the burghers of the Old Town to propose a reduction of the ghetto and to complain about its expansiveness.

In 1729 there was a census of the Jewish population and of the buildings of the ghetto. 333 dwelling houses inhabited by 2,335 families and 30 public buildings were registered. One of the unpleasant restrictive measures of the period prohibited anyone other than a first-born son to start a family, as the permitted number of Jewish families in the whole country was strictly limited and was not to be exceeded.

During the reign of Maria Theresa, in December 1744, there was a new attempt at dealing with the problem of the Jewish population in a radical way by means of their expulsion from Prague and the entire Kingdom of Bohemia. An alleged cooperation of the Jews with the enemy during the Prussian occupation of Prague in the autumn of that year was the pretext for the above plan. The exodus, however, did not prove to be easy due to various financial and business connections. Nevertheless, by mid 1745 all inhabitants of the Jewish ghetto had to leave Prague. Some of them settled in the nearby Libeň Quarter and other hamlets in the vicinity of Prague. There they lived until 1748, to witness the revocation of the expulsion order. They found their houses in the ghetto, which had been vacant for two years, looted. Soon after the renovation had been completed and life in the Jewish Town started to function normally again, a fire of 1754 destroyed 190 houses of the ghetto. The synagogues, the Town Hall and the hospital also burnt down.

The enlightened reign of Josef II brought about significant changes for the Jewish population. Jews were no longer banned from public schools and the university, they were entitled to acquire property outside the ghetto, to become artisans’ apprentices and entrepreneurs. On the other hand, many earlier discriminatory measures, such as the limited number of permitted Jewish families in the country, remained effective, as well as the obligation to pay extra taxes and fees. Many barriers, however, which had isolated the Jewish community from its Christian counterpart were eliminated. The Jews no longer had to bear any special identification marks and they were free to move house within the territory of the entire city of Prague. Gradually, wealthy Jewish families began to leave the ghetto, and this was apparent in the course of the 19th century in particular.

The first half of the 19th century was a period in which the tradition of this urban settlement saw its heyday as a Jewish ghetto. In 1848 the Jewish community was granted equal civil rights and in 1850 the territory of the ghetto was officially annexed to Prague, bearing the name of Josefov (to commemorate Josef II), and as a new quarter it was marked by the Roman numeral V. Only poor people and orthodox Jewish families continued living in the ghetto; according to the official statistics, by 1880 the number of Jews settled in Josefov dropped to one third or one fourth of its previous total.

The territory and character of the former ghetto have been depicted so precisely in the course of the 19th century that we are able to visualize it. The most accurate portrayal of the Jewish Town can be seen in Antonín Langweil’s famous model of Prague, which depicted it in the second half of the 1820s. More depictions followed in the years before the planned clearance in terms of photography (Jindřich Eckert, Jan Kříženecký), as well as in terms of art (water-colours by Václav Jansa, oil-paintings by Jan Minařík).

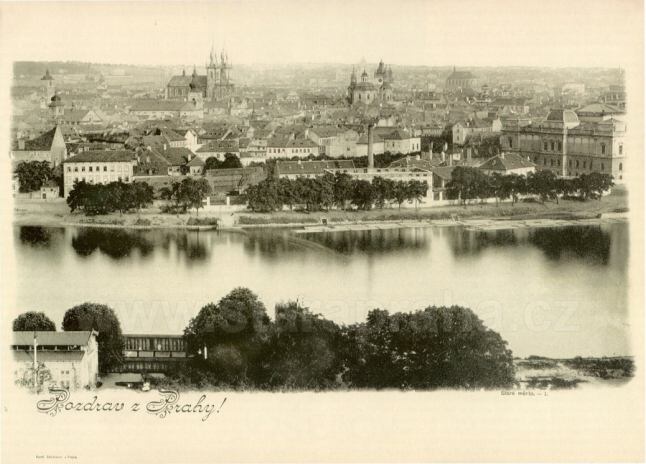

In all panoramic views the former ghetto differs from its neighbourhood by the higher density and narrowness of its buildings. More detailed views depict a distinct quarter, with a number of crooked lanes and cul-de-sacs. Its complexes of buildings in the courtyards and on the corners are bizarre and picturesque. Various buildings reveal their mediaeval origins, even though the fire of 1689 destroyed most of the decorative elements of the Gothic and Renaissance facades. Baroque hardly ever passed the boundaries of the ghetto. Smooth facades and facades modified by rigorous Neo-Classicism prevail in the ghetto. The largest houses are located on the corners, as if they served as buttresses for the others, the street level, descending to ground-floor level and then ascending steeply to reach the second or third storey, bends and allows narrow passage ways and cul-de-sacs to interrupt its flow. The cul-de-sacs mostly evolved from original courtyards, which were built up with smaller houses because of a shortage of space. This is how the ghetto grew denser and denser. In the courtyards one can encounter an odd blend of annexes, often Baroque and Neo-Classical built-on galleries, and a curiosity of the ghetto’s architecture - exterior staircases covered with oblique roofs. Numerous mansions have two or three entrances, each of which bears its own land-registry number. Some houses have therefore two or even three numbers. This fact relates to a special feature of the ghetto in terms of property rights, where the right of property to individual houses was not divided ideally, but physically.

In the last quarter of the 19th century the overpopulated quarter of Josefov was in a state of disrepair. The houses were neglected and uncared-for and hygiene was extremely primitive. Due to the proximity to the river and the low altitude of the ghetto, flooding was quite frequent. The basements of the houses were humid and the overall environment of Josefov was unhealthy, with sickness and death rates higher than the average, both being substantiated by statistics. In the wake of this untenable situation, and following the example of other European cities, the Prague Municipality opted in the 1880s for the most radical solution, namely the clearance of all old buildings in Josefov.