MILAN DEGEN: VYŠEHRAD

No other locality in Prague, or even in the Czech Republic, is the subject of so many legends as Vyšehrad. It towers on a rock, as if growing from the right bank of the Vltava River. Today, a substantial part of the rock abounds with trees and bushes, and turns yellow with alyssum flowers every spring. Vyšehrad, veiled in a haze of ancient historic events, about which nothing has apparently ever been written, evokes mystery which can be sensed here at every step. This feeling of mystery emanates from the Julius Mařák painting, and it can be heard in the harp tones of the symphonic poem Vyšehrad by Bedřich Smetana, as well as in the verses of the poets Karel Jaromír Erben and Julius Zeyer.

According to myths and legends, Vyšehrad was the residence of the judge Krok, Princess Libuše, Přemysl - the founder of the first ruling dynasty in Bohemia - and his successors. The reality, however, was different. Archeological finds pertaining to the historic period date back surprisingly only to the 10th century. The foundation of a Slavic walled-in settlement on the Vyšehrad rock is probably associated with the gradual decay of hill settlements in the Prague basin and its surroundings, places like Šárka, Butovice, and Zámka. The walled-in settlement on the rock, originally perhaps called Chrasten and formed approximately in the first half of the 10th century, was obviously initially of a military character but it is not known who founded it.

The first authentic evidence about Vyšehrad was brought to light in the form of Přemyslid dinars from the Vyšehrad Mint, dating back to the years 992-1012. If Vyšehrad had not been the walled-in settlement of a Bohemian tribe - or of the Přemysl clan - from the beginning, it unquestionably was by 992 at the latest. The first written records concerning Vyšehrad are in Cosmas’s Chronicle dealing with 1003 and 1004, when Jaromír ruled in Bohemia. After being enthroned as the Prince in Prague Castle, he was also proclaimed the ruler of Vyšehrad, which proves that the importance of this site was far from marginal. The space that the early medieval walled-in settlement (surrounded by earthen mounds with a wooden reinforcement) occupied, was far smaller than today’s area. South of today’s Collegiate Church, an independently fortified Prince’s courtyard with a mint, quarters for military companies, stables, and other buildings were found. Outside this area stood the early romanesque Churches of St Clement (Kliment) and (most likely) of St Lawrence (Vavřinec), as well as a number of log-cabins for local inhabitants, bound here by their work. The clergy, monks and others, too, must have had their dwellings here.

Vyšehrad remained in roughly the same state until the second half of the 11th century, when Prince Vratislav II, after disputes with his brother, the Prague Bishop, chose it to be his permanent residence. (He ruled in the years 1061-1092.) He began to rebuild Vyšehrad as a stone romanesque castle, suitable for its new function as the prime fortress of the country. Under Vratislav, the first Bohemian King from 1085, several churches were built: the Rotunda of St Martin; the Basilica of St Lawrence (on the site of an older construction); and, most importantly, the romanesque Collegiate Basilica of St Peter and St Paul (Petr a Pavel), which the sovereign had founded in 1070 and caused to be removed from the jurisdiction of the Prague Bishopric so that it became subjected directly to Rome. Vyšehrad became an important trade centre in Vratislav’s time. This had a considerable impact on housing development in the settlement round the castle, below the north slope of the Vyšehrad Rock (this settlement did not originate before the 10th century) and also on the settlement called Mezihrady (literally between castles) along the road linking Vyšehrad and Prague Castle.

As the 11th dissolved into the 12th century, Vyšehrad had acquired a Romanesque castle which, with its stone walls, royal palace, four or five sanctuaries, and other components, competed with Prague Castle, which it even surpassed in security and extent. Despite this, the sovereigns moved back into Prague Castle after 1140, and Vyšehrad began to fade from Czech history. The former King’s residence slowly became the domain of the Catholic Church - under the control of the Chapter, which was governed by the Provosts of Vyšehrad. The most prominent of them, Petr of Aspelt, who was at the same time also the archbishop in Mainz, was counsellor to the last Přemyslids and to Eliška Přemyslovna. She was the mother of Emperor Charles IV; she lived in Vyšehrad towards the end of her life, and died there in 1330.

In fact, the reign of Emperor Charles IV (1346-1378) signalled the return of Vyšehrad to the historic scene. After the foundation of the New Town (1348), Vyšehrad was integrated into the Prague defence system on the right bank of the Vltava river. In the years 1348-1350, the periphery of the peak of the Vyšehrad Rock was fortified by a new Gothic brick wall with two gates. The bigger, to the southeast, later called Špička, was built at the most vulnerable position opposite Pankrác. The other gate, oriented towards Podvyšehradí (literally under Vyšehrad), was called Pražská (i.e. the Prague Gate), later Jeruzalémská. From then on, a thoroughfare through Vyšehrad became the only main access to Prague from the south and around this a marketplace arose near the Rotunda of St Martin. A road started from the Prague Gate, linking Vyšehrad with the old market street in Podvyšehradí (today Vratislavova). Under Charles IV, the walled-in settlement was rebuilt into a Gothic castle; a new palace, houses for the castle servants, and further churches and chapels were constructed. According to the new Coronation Code, Vyšehrad was to be the initial site for the celebration of the Coronation of Czech Kings. After 1346, the construction of a more capacious Gothic Collegiate Church, designed to replace the original romanesque church, was commenced. This project, however, was never finished, and a rather motley Romanesque-Gothic church complex therefore arose, reaching over 110 m in length. Nothing could compete with this in Prague of those days but it is now only half that length. Practical considerations dictated the introduction of a piped-water system in Vyšehrad(around 1361); a town-hall was built (about 1400), and later on a school, which suggests that the Vyšehrad area was inhabited by significant numbers of townspeople, as well as by members of the Chapter and the castle residents. The 14th century also signified the transformation of the buildings of Podvyšehradí. Dozens of burghers’ houses were constructed there, many public buildings, e.g. baths, a hospital, a shelter for the poor, as well as new ecclesiastical buildings came into existence.

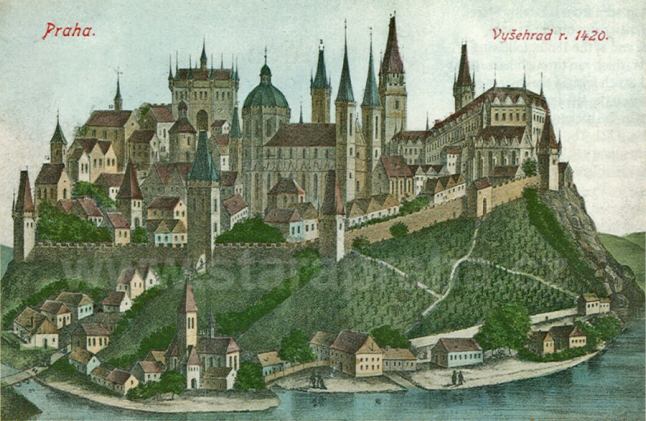

Towards the end of the pre-Hussite era, the Gothic Vyšehrad and Podvyšehradí must have made a ravishing impression. In 1420, however, the whole complex was suddenly destroyed, and thus disappeared from history for decades. After the battle at Pankrác, where the Hussites crushed emperor Sigismund’s troops, and after the King’s garrison (including the Chapter’s members) had left Vyšehrad, an enraged crowd stormed inside, plundering and smashing everything that was in their way. Almost all the buildings, including the walls on the side facing the New Town, were destroyed, with the exception of the Collegiate Church and the Rotunda of St Martin. Podvyšehradí, too, ceased to exist, after it had been burnt down by the people of the New Town. Vyšehrad, with its surrounding settlement, turned into a waste land with dilapidating ruins.

In 1448, the troops of Jiří (George) of Poděbrady, who later became the Czech King, penetrated Vyšehrad without a fight, and subsequently quickly conquered the whole of Prague, without bloodshed. Several years later, a decree was issued making it possible to acquire plots of land free of charge, with tax exemptions for those who would build a new house or reconstruct a ruined one. (The original small settlement never had more than 50 houses.) This attracted many people although they received no written confirmation. Around 1476, these new settlers of the so-called Upper Town established their own self-government, built a town hall, and strove to attain the status of a royal borough. For this purpose, a new municipal code was drafted after 1505, apparently after Podvyšehradí (the Lower Town) had legally separated from the Upper Town, and passed into the possession of the Chapter. The Upper Town retained its independence until 1528, when it also fell under the authority of the Chapter as a serf borough by the decree of emperor Ferdinand I. Long after that, people in bondage in Vyšehrad were fighting with the Chapter, the fight being partially motivated by religion; while the Chapter was Catholic, these people were Utraquists.

From the second half of the 15th century on, the walls and the Collegiate Church were repaired. Howewer, in 1503 a part of the church vault fell, and the arching and other reconstructions had to wait until 1565. As the 16th turned into the 17th century, a new presbytery and sacristy came into existence. Later, the Church was substantially shortened, compared with its romanesque-Gothic shape, and it then adopted approximately the current groundplan.

At the end of the Thirty Years’ War (1648), the Swedes bombarded Vyšehrad, and destroyed walls and a number of buildings. This intensified the need for reconstruction into a Baroque fortress, the first stage of which had been underway from 1621. The Baroque style, which interfered with the architectural appearance of Prague more and more from the beginning of the 17th century, proved to be no less disastrous for Vyšehrad than the demolition of the Castle in 1420. It spelt the absolute doom of the Upper Town, all the population having been moved out around 1655 - almost without exception to Podvyšehradí. At the same time, the military administration completed the Táborská Gate and a big armoury in the district of the former King’s Courtyard; in the years 1676-1678, walls with bastions were added. One of the important constructions of that time in Vyšehrad is Leopold’s (French) Gate, built before 1670. During the French occupation of Vyšehrad (1741-1742), in the course of the war over the Habsburg inheritance, mounds with palisades were erected and casemates were established below them. (The construction was supervised by the French architect Berdiquier.) The casemates were linked to other secret underground passages which were said to go down the slanting terrain, even below the Vltava River bottom, continuing under the river and through its left bank, allegedly leading as far as Prague Castle and the Břevnov Monastery. Utopia? - perhaps so, perhaps not. Our ancestors were in many fields far more qualified, diligent (also enigmatic) than we are willing to admit. In 1678 a separate belfry was built in the cemetery together with a church - for a long time the only dominant feature in Vyšehrad. After that, in the years 1723-1729, the reconstruction of the Collegiate Church was realised according to the design of František Maxmilian Kaňka, influenced perhaps by Giovanni Santini. The residents of Vyšehrad in the Lower Town constantly strived to break free from the bondage of the Vyšehrad Chapter, so they established their own town hall around 1765. Eleven years later, however, during the dangerous peasants’ uprisings, the Chapter issued a new Municipal Code, which made the conditions of serfdom even more severe.

Towards the end of the 18th century, Vyšehrad’s Baroque fortress was already antiquated from the military point of view. Despite that, new cannons appeared there during Napoleon’s invasion of Central Europe but, in the end, they were only fired for practice. The Cihelná (Brick) Gate, ranking among the most beautiful buildings in Prague in the French Imperial style, was built near the demolished Jeruzalémská Gate in 1841-1845, at the insistance of earl Karel Chotek, in connection with the modernisation of the thoroughfare running through Vyšehrad. The political situation after the revolutionary year 1848 helped Vyšehrad and its neighbouring area to gain independence. Vyšehrad kept the status of a self-governing town until it merged into Prague as its sixth quarter in 1883.

After Austria lost the war with Prussia in 1866, Prague was proclaimed an open city by the decree of Franz Josef I, and its position as a fortress was abolished. This, of course, also applied to Vyšehrad. However, it remained under military administration until 1911, when the Prague Municipality acquired the grounds and the walls.

In the years 1885-1903 the Collegiate Church was rebuilt in the spirit of architectural purism with a Neo-Gothic appearance, to the design of Josef Mocker. The Baroque belfry in the cemetery was pulled down, and in the years 1902-1903, two massive Neo-Gothic spires were built by František Mikš on the west side of the Church; they are disproportionately large, considering both their mass and height, and they are Vyšehrad’s dominant feature today. At about the same time, the reconstruction of the adjacent cemetery was underway, according to Antonín Wiehl’s design. The area of the cemetery was extended in several stages, and Slavín - a memorial for the most meritorious personages of the Czech nation - was built in 1889-1893. The poet Julius Zeyer (1901) was the first person to be buried there, and the last, so far, was the conductor Rafael Kubelík (1996).

The need to connect inner Prague with the settlements beyond Vyšehrad forced the construction of an elevated embankment, and a tunnel through Vyšehrad rock, in the years 1902-1905. Consequently, the small picturesque houses at the foot of Vyšehrad disappeared. In their place, new Cubist houses by Josef Chochola were erected in the years 1911-1913, later on other, largely rooming houses. Cubism in architecture is uniquely Czech. Cubist houses do not exist anywhere else in the world.

In a park south of the Church, three monumental sculptural groups of figures from Czech mythology (Lumír and a Song, Záboj and Slavoj, Ctirad and Šárka) by Josef Václav Myslbek were erected in 1948-1970; the park had been founded on the site of the extensive Baroque armoury, which had burnt to the ground in 1927. The gigantic statues originally stood on huge pillars along both sides of the Palacký Bridge. During the bombing of Prague by the American Air Force in February 1945, the sculptures were damaged and a fourth group, the most impressive, representing Přemysl and Libuše, was completely destroyed; in 1978, a faithful copy was installed in Vyšehrad, and thus Myslbek’s imposing collection at last became complete. Vyšehrad was proclaimed a national cultural monument in 1962.